As someone who played games in the late 2000s and early 2010s, I have played Call of Duty.

Much has been written about the revolution Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare was to the gaming landscape, catapulting creators Infinity Ward and publisher Activision to great heights, but also changing the way games are made and played even to this day.

For many years CoD was the gaming king. There were an other major shooter hits around the same time, with Halo 3 for the Xbox 360 selling over 14 million copies in 2007 and Battlefield: Bad Company releasing one year later.

Battlefield and Halo are big series in their own right, but Activision and the teams of Infinity Ward and Treyarch started a tag-team trend of releasing a bestseller game every year.

Two years after CoD4 and the monster smash-hit release of Modern Warfare 2, other developers took the sign that the modern military shooter boom was here to stay and so planned their own “Call of Duty Killer” games.

Electronic Arts, once the founder and leader of the military first person shooter market with Medal of Honor, had been seeing moderate review scores and sales, but nothing compared to CoD. There most recent title at the time, Medal of Honor: Airborne, released a few months before CoD4.

But when ‘modern warfare’ became the genre du jour, EA looked like they were literally stuck in the past, only releasing games set in World War II. So after a three year hiatus they decided to bring Medal of Honor out of the past and challenge Call of Duty in a modern war.

And now over fifteen years later I want to look at this game, what succeeded, what failed, and what it tried to do.

Heroes Aboard: A Look Back at Medal of Honor (2010)

While Call of Duty wasn’t the first game set in the modern day, it was the first to make a big impression and be accessible to a wide range of gamers.

Part of CoD4’s cultural mass adoption is both its time and place. Releasing in 2007, making a note on two recent hazy military conflicts that had seemingly outlived their welcome, it took the imagery of modern warfare yet left the political wrangling to the side.

It’s clear even when looking at the shift from the first Modern Warfare to Modern Warfare 2. MW2’s first mission, “S.S.D.D.”, lists the location as Afghanistan. In Modern Warfare, despite other locations such as the Bering Strait and Western Russia being listed in their opening cards, the ‘Middle Eastern’ locations are never named.

It’s a small distinction, but a notable one; CoD did not want to tangle with ongoing conflicts.

For the majority of World War II games, a lot of the gameplay was inspired by real life locations and events. So when CoD decided for Modern Warfare it would stay quiet on the current wars, Medal of Honor played an interesting card and set their game during the invasion of Afghanistan.

The story would be based around “Operation Anaconda” in March 2002, the second largest operation to that point in the War in Afghanistan. The game retold the events surrounding a two-day operation, playing off multiple angles and operators.

While names had to be changed and events streamlined, the plot sticks close enough that anyone reading the documentation of the operation can match the real operators to the characters.

It’s an interesting hook, an eye-catching and novel move, yet many believed it was disrespectful to play a depiction of an ongoing conflict.

Controversy was further highlighted when Amanda Taggart, senior PR manager for EA commented, “Most of us having been doing this since we were 7 – if someone’s the cop, someone’s gotta be the robber, someone’s gotta be the pirate and someone’s gotta be the alien…In Medal of Honor multiplayer, someone’s gotta be the Taliban.”

Immediately bans were called for across the world and eventually the Taliban were renamed to Opposing Force in-game, but the vibe had been set, MoH was going to stay in the real world. There hadn’t been many like it before, the only high-profile game that tackled a similar aspect was Six Days in Fallujah set in the Iraq War, which was ultimately cancelled in 2009.

So with the context set up, let’s have a look at the gameplay and plot.

To discuss how Medal of Honor plays and presents its story we must continue to talk about Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare.

But why am I still comparing MoH to CoD4? MW2 had come out the year before MoH. Even comparing it to Black Ops would be a more balanced argument, as both came out the same year and faced a similar uphill battle as the “new” face of the franchise.

It’s because for all intents and purposes, Medal of Honor’s reference is Call of Duty 4. The grounded setting (with a dash of real-world politics) and a mixture of both regular infantry and special forces; that combination catapulted CoD into the mainstream.

MW2 and Black Ops moved the series into a larger-than-life action movie; thrilling for sure, but for those looking for a more realistic depiction of war, CoD was slowly slipping away. So there was a prime spot of gaming real estate for Medal of Honor to quickly step into by catering directly to CoD4 fans.

CoD4 has a total of twenty levels, including both non-combat missions (“The Coup” and “Aftermath”) and discounting “Mile High Club” (as it is not connected with the story).

Medal of Honor has only ten levels, yet they are significantly longer and both games take around the same time to beat (around 5-6 hour mark).

I’ve written previously about CoD4’s excellent pacing, placing the player first in the boots of a Special Forces team member and executing stealthy and surgical engagements before ratcheting up the ante for regular infantry roles. It is the perfect balance of the scalpel and the sledgehammer.

Medal of Honor for the first time in its history was going to have several playable characters. Previous games had been focussed on a single character. The multiple characters approach feels like a direct response to Call of Duty, which had been doing character swaps since their first game.

Those character swaps allow for the excellent pace development and so just like CoD4, MoH starts with a surgical strike by a team of special forces before moving to Big Military engagements.

After an ominous opening where we listen to newscasters and street-level civilians reacting to the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center we flash-forward to an airborne insertion that goes horribly wrong (copying Black Hawk Down) to then a night-time silent rendezvous in Afghanistan two days prior.

It’s a little jarring, but a standard enough opening and echoes CoD4’s first mission, “Crew Expendable”, where a top special forces team readies for an infiltration.

The mission opening also gives us the first bit of chemistry between our Navy SEAL (Neptune) teammates; Mother, Voodoo, Preacher, and player character Rabbit. The codenames are cute and obviously inspired by Soap, Gaz, Roach, and Ghost from the Modern Warfare trilogy.

As Neptune drive into the town in separate vehicles, Voodoo turns off Rabbit’s music on the stereo and makes some jokes with Mother over the radio. The nighttime drive becomes intense as they weave slowly through tight-knit streets and are momentarily stopped by a shepherd and his flock (who Voodoo berates in about three different languages).

But suddenly, bang, whizz, flash, gunfire and explosions come from all angles as Neptune gets split up and Voodoo rams his car through a couple of roadblocks until he and Rabbit can get out safely.

While the mission starts okay with the nighttime drive it quickly loses any tension or build up just by how LONG it is. The mission, titled “First In” from start to full control to the player is OVER SIX MINUTES. It is painful to sit through.

“Crew Expendable” from CoD4 goes from setup cutscene to weapons free in just over a minute.

It’s also not the best start to the game. It’s a lot of explosions, gunfire, dark pathways and corners. Even with cool night-vision goggles the level seems so devoid of fun; the most generic corridors and streets with the most stereotypical of enemies. It reminded me more of the first mission of Black Ops that released the same year; gunshots, grenades, hysterical shouting, screeching cars, but nothing that would tie it all together. In the end it becomes exhausting.

So the player goes through the standard FPS starter lines; point-click shooting, waiting for friendlies to open doors, primary, secondary, melee, all that good stuff. Players can kick in doors, which is a new feature, but is nothing more than an extra animation.

The truly new feature that Medal of Honor brings to the 2010-FPS landscape is movement. If players sprint they can slide when holding the crouch button ostensibly to get into cover. While in cover (or general gameplay) players can use the lean button to peek out and shoot in any direction they want.

These are two great mechanics, perfectly complementing each other and changing the way I would play the game. All FPS players are used to waiting behind cover before either playing a game of whack-a-mole or having the sacrifice their health in an effort to push forward.

With Medal of Honor the slide encourages pushing forward as well as evasive manoeuvres. Sliding between degradable cover from oncoming fire or out of the splash range of a grenade feels great, evoking third-person-shooters in their style but maintaining the traditional FPS. The slide also drops players into a crouch or prone, ensuring player health instead of getting shot while finding cover.

If the slide is for aggression, the lean is for defence. While at first you will use it to quickly snap over or around cover, its true usage comes when taking enemy fire. While using the lean button the movement stick becomes your axis, keeping you still but allowing you lean in every direction.

This can be exploited to great effect; say your degradable cover is chipped away until you are visible if you are crouching. But if you use the lean button and lean “downwards” the player can effectively still use the remaining cover. When a player realises this it then compounds the slide as you start to see new possible cover places that can be used with the lean.

It’s a great tool for enemy placement as well. You can quickly lean out of cover and see where the enemy are and get ready to counter instead of having to continually stand and crouch like other FPSes. Lean and aim are bound to different keys allowing for quick battlefield surveillance and response with a snap of the fingers. It’s also nice that that you hold the lean button rather than tap it to engage and release. It feels much more responsive and allows for fast-paced fighting.

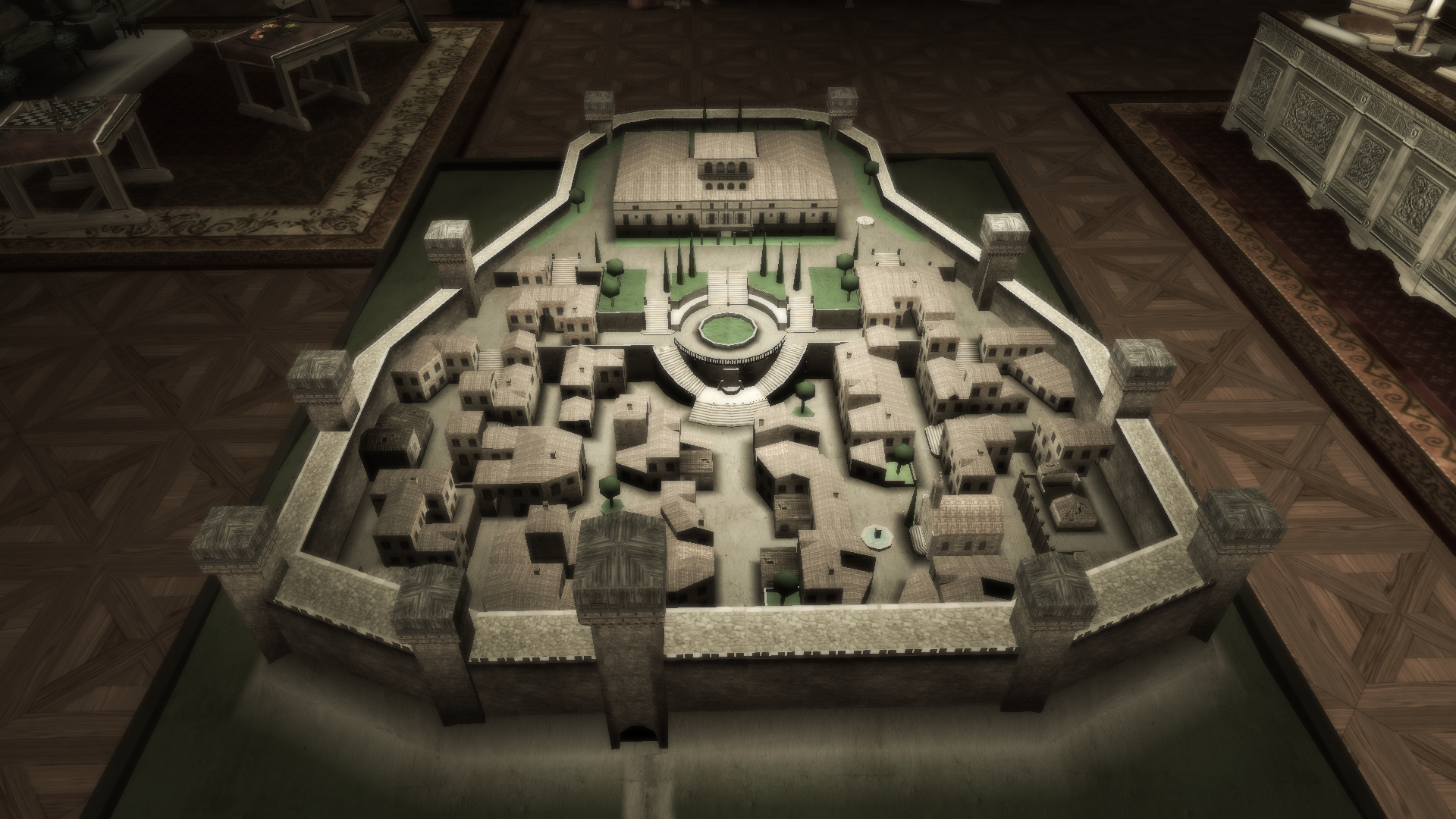

Back to the first mission. Gameplay livens up a little bit once the four members of your squad rally together and head onto the rooftops of a little fort, eventually doing battle across a town square and playground. It’s an interesting location; a nice solid arena for gameplay while giving a hint of life before the war and also highlights the great landscape of Afghanistan in the background.

If you ask people what is the landscape of Afghanistan most people would probably say deserts and sand-blasted cities. While we do get to trek through some wadis and battle in ancient desert forts, the game does a tremendous job of showcasing the wide-ranging beauty of the “Graveyard of Empires”.

Snow-capped mountains, wide gorges, dense forests, it’s stuff that isn’t immediately associated with Afghanistan, but is 100% true to the location. The little things in said landscape too; goat trails, pilgrimage posts, Soviet wreckages, concealed nests and doors, they give the space a sense of real life, of centuries of warfare and people learning to exist in the harshest of landscapes.

After surviving a booby-trapped explosive corpse the team find their contact Tariq and begin debriefing him. During the debrief we also get a slight injection of politics into the story. When Voodoo starts to interrogate Tariq about the ambush and whether Tariq is on the side of the Taliban or not, Tariq responds;

“Please. I have a daughter. I want her to go to school. I want her to be a person, to have a life. Do you not understand?”

It’s a far cry from Call of Duty and Battlefield whose reasoning for going to war is not even some vague notion of “freedom” or “security”, just head to a vaguely Middle Eastern/Eastern Europe looking area and shoot everyone that you see.

It’s a small moment, not even 10 seconds long, yet it makes a case for why we are here and what is sacrificed if the US leaves. Then BANG, straight into the second mission, “Breaking Bagram”, a more high-intensity mission about retaking a Taliban-held airfield that will be the main base for the invading force.

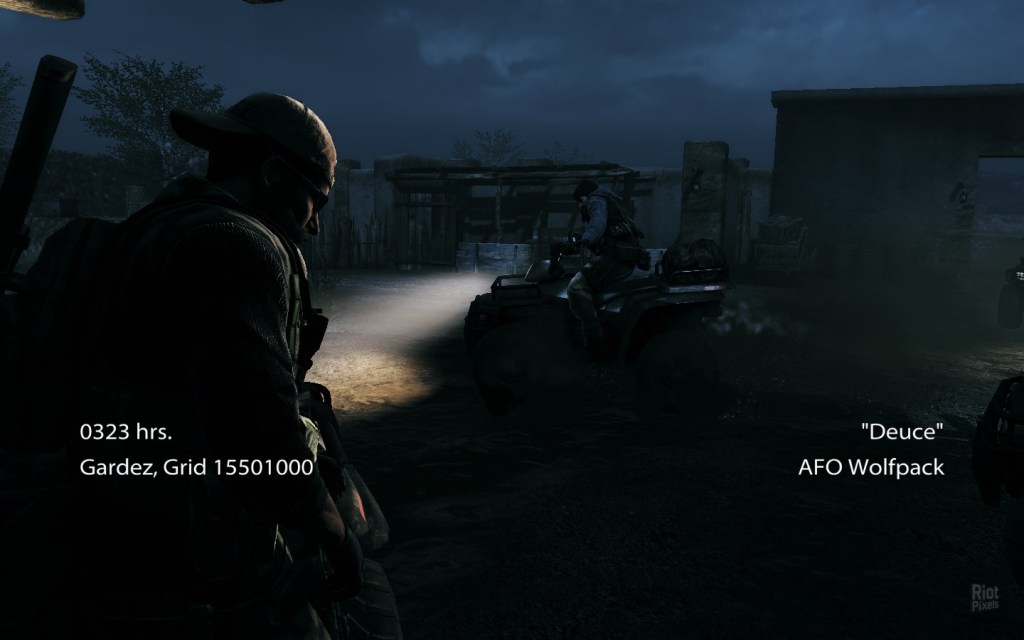

I wanted to also take a moment here to mention the tags at the beginning of each level. Obviously plucked from CoD, each levels starts with the “name” of the character, their team, the local time and the location. However they are so bland, simple white text on top of the screen that they almost feels like placeholders.

They are in the same position on-screen as the CoD text, but they don’t have any animation, no cool SFX or visual design, they just appear and then get immediately lost among the visuals when the gameplay picks up.

The second mission starts explosively with a daybreak siege on the airport with Rabbit riding shotgun in a pickup truck and spraying at enemies with a huge light machine gun. Arriving at the gate of the airport the calvary splits up. While the Western-backed Afghan National Army storm the front gate the Neptune boys circle around and work through the mortar fields and sniper nests.

The opening is fun and gets the blood pumping, but after getting out of the truck and heading out on foot the level falls back into that generic hallways and spaces like the first mission.

Even something like a missile strike; where MW2 would have you rain down Predator missiles yourself here in Medal of Honor you just point a laser pointer at a single building and then an explosion happens. It feels so anticlimactic.

But after sliding and shooting we finally get to a nice open arena style again, with the radio tower as our goal. Sniper and rockets keep raining down if you stay still for too long or out in the open so it encourages pushes and slides so that you can reach the tower. It’s a cool set-piece and again a great ending to a somewhat drab mission.

The next cutscene shows the Big Military landing and setting up in the airfield and becoming the Command Center for AFO Neptune. We get some back and forth between the young colonel in the base and an older general safe in his office in the USA. I don’t know if these are based on real people, but it’s the most Hollywood-cliche “young buck/old-hand” story and a serious weak point in the narrative.

Onto the third mission, “Running With Wolves…”, and our first character swap, stepping into the boots of Delta operative “Deuce” and the team AFO Wolfpack.

I did research for this piece to see the difference between Delta and SEALs; they are both top military teams, SEALs seem sledgehammer-style and Delta are more scalpel. While it’s interesting to see so many different facets of the giant machine that is the US Military there really isn’t much of a big distinction at this moment of the different tasks the teams will be performing.

We first meet Delta during Tariq’s debrief at the end of the first mission. It’s cool to see these top teams working together on a bigger goal even if it just via radio commlink.

The Delta boys are actually the poster boys for the reboot game. Deuce’s team mate, Dusty, is the guy on the cover of the box, he got all the marketing, he’s the only character in the game that actually has a distinct character all from that glorious beard (an alumi of the Captain Price School for Military Facial Hair I see). He’s obviously modelled of the real-life Delta operatives that were photographed during the battle of Tora Bora, the two-day event that the story is retelling.

Deuce along with team members Dusty, Panther, and Vegas are outfitted with stealth ATVs and are tasked with monitoring Taliban shipments. The ATVs is our first real new mechanic, driving across the rocky terrain at night…and yet it’s not fun.

Even when having to stop and douse the headlamps so a patrolling group don’t see you, it never feels tense enough. I would say that stealth missions work best as a solo operative and not being hampered by other soldiers.

But CoD4 and MW2 had great stealth missions with a similar objectives, “Cliffhanger”, and “All Ghillied Up”, often highlighted as two of the best levels in the entire series. “Running With Wolves…” should feel the same; sneaking through the dead of night with hundreds of fighters in the surrounding area and having to use speed and silenced weapons to keep ahead and undetected.

Well, we drive around, shoot up some towns here, snipe a couple far-away enemies there and plant trackers on a few trucks. It was here where I was starting to think this is a boring game. CoD is often lambasted for its railroading approach to its campaign, but at least every stop is a fun little excursion. This just felt bland.

Onto the next mission though and back to the Navy SEALs as they begin to push into the mountains. The opening is cool, sneaking through the tall grass near a goat herder, who Voodoo quietly puts to sleep and revealing he has a radio to inform the Taliban of approaching US forces.

It’s in this mission where the real and overwhelming size of the Taliban fighting force facing the US is revealed. Neptune encounter scouts (using fires and smoke plumes to communicate) before finding AAA guns that intelligence missed. This missions is quite fun; moving from small sharp encounters to then longer more protracted battles, having to use cunning and stealth to thin out forces before charging headlong into battle. It mixes up the style of gameplay, which is refreshing.

The scenery is also stunning, looking over the mountain ranges and wide valleys, snow and pine trees litter the landscape, entering small caves and nooks that have the previously mentioned fire stoves, starting the mission in the dead of night and seeing the day break as you reach the final battles, it is something rather special.

It also features a nice little connection to the previous Delta mission. Deuce and Dusty put trackers on vehicles in that mission and Neptune are able to call in airstrikes on those said vehicles during their battle. It’s small and we don’t get to shoot the missile, but it’s something.

Back at the airbase, communication errors lead to the US firing on friendly Afghan troops and opening a hole for the Taliban and Al Qaeda to exploit. Again, it’s highly-stylised, probably fictionalised and is the worst part about the game. To plug the gap in their forces the US deploys the Rangers, the closest thing to regular boots-on-the-ground soldiers in the story in their first level “Belly of the Beast”.

This is the best mission of the game, hands down. I felt this way when I first played the game, when I replayed it for this retrospective, and it seems to be the general consensus of the YouTube review crowd too.

The mission starts with a fleet of Chinook helicopters flying into the zone and the crass captain making clichéd remarks like he is an air stewardess and calling the men in his platoon “ladies”. The music ramps up as the helicopter lands and the troops rush out into defensive positions.

The privates rattle off calls of “clear” and the whole thing looks like a damp squib. As the soldiers resign themselves to the long walk to the OP, a rocket streaks across the sky and hits one of the departing Chinooks, sending the bird tumbling down right on top of the recently departed soldiers.

Gunfire erupts and mortar shells start flying as the troops realise they have already been marked in a kill zone and so run for cover to the walls of a nearby wadi. For the first time it feels like you’re on the back foot, having to shift cover to cover and take shots when you can.

The troops start making their way into the wadi to reach the OP, where the game blossoms into one of the most intense gun battles I’ve ever played through. The US are heavily outmanned and outmanoeuvred with enemies streaming down the mountains into the wadi, just visible by their silhouette through the midday sun haze.

The only trump card the US have is the bigger weaponry. The player character is the light machine gunner of the squad, carrying a scoped machine gun with 200 rounds ready to fire. While it can pick off headshots of far away enemies its main purpose is suppressive fire, halting the enemy from gaining ground and allowing your own squad to push forward.

Talking of that machine gun, Medal of Honor has some of the most powerful sounding guns I’ve heard in an FPS. Every gun from the silenced pistols to the snipers, shotguns, and rifles, nearly every gun has an excellent “pew” to it. The machine gun is no different with a nice hefty bass giving the the constant ratta-tat-tat a visceral quality. Compared to the Call of Duty of the same time, Black Ops, in which every gun sounded like a toy pop-gun, Medal of Honor really has quality sound effects.

So the troops starting making their way to the OP clearing small villages of fighters and finding old relics of the Soviet invasion. It’s a nice nod to the real historical and political aspects of the location and possibly a history that players may not have known about.

I didn’t know much about the Soviet invasion into Afghanistan, but this throwaway line made me interested in learning more. Anyone interested should read Boys in Zinc by Svetlana Alexeivich as a great non-fiction work focussing on the soldiers and their families.

The level peaks in two locations; first is a mounted heavy gun encampment that is keeping other US troops from securing their objective. The squad is tasked with storming the placement, but the player is told to hang back. Being the light machine gunner we must lay down suppressive fire so the other teammates can get close and mark it for an airstrike.

It’s a unique premise after the years and years of both Call of Duty and Medal of Honor making the player character be the sole warrior to defeat the enemy. Now you’re just working as a cog in a machine and is refreshing to see these different facets be included in the game.

Not to mention the gun placement sometimes turns on the player and can quickly degrade the cover you’re hiding behind meaning we have to continually move while trying to deliver suppressive fire.

When the gun placement is finally marked and the rockets rain down, earth is kicked up and the entire screen goes dark for a few seconds before the sun breaks through and all that is left is the haze of debris and dirt. It’s a fantastic close-range look at the destructive capabilities of modern artillery, but while the squad members marvel at the explosion they don’t cheer or whoop like frat boys seen in the previous year’s Modern Warfare 2.

The second peak is the end of the mission. While securing a landing spot for medical transport, the squad are rocked by an IED, an improvised explosive device. Surprisingly the entire squad survives, but the explosion draws the Taliban’s attention and quickly the four-man squad are facing overwhelming odds.

The squad taking refuge in the only cover at the location, a mud hut that slowly deteriorates with each bullet. The player is tasked with aiming just at the enemies with rockets, but soon Taliban fighters try to enter the hut and so the player has to switch between long range precision shots and short range reactive bursts.

Over time your ammo stocks start to dwindle yet the onslaught never stops. You switch to your pistol and pick up random AKs from fighters that got too close and keep the wave back as long as you can. Your radio man is trying in vain to call for assistance, but eventually your squad leader tells him to stop. There is no way that help will get there in time.

Player characters have died before with Modern Warfare 2 featuring three iconic death scenes in gaming. Yet all were in “cutscene” mode, no agency from the player. Halo: Reach, released in the same year as Medal of Honor also had the player facing overwhelming odds and finally succumbing to their wounds.

Another EA staple, Battlefield, would try something similar with its opening for Battlefield 1 (which I also wrote about).

The moment hangs there for a good few seconds, letting the player’s imagination fill in how the end will look like, how it will feel.

Then a rocket sails overhead and hits the oncoming Taliban fighters. More rockets fire off followed by heavy machine gun fire. Two Apache helicopters come in at the last moment to save your life and forcing the Taliban fighters to retreat.

It’s a great moment, holding long enough to think that all is lost to then see the helicopters in gameplay come overhead and seeing the Taliban chased off. The squad are more than entitled to cheer and whoop at this moment as we shift into the next mission…and into the seat of one of the Apaches.

The Apache mission is a great break from the on-foot sections. We only control the weapons system for the helicopter, but that allows the computer to perform some beautiful low-flying sweeps inches from the canyon floors, or breaking over a peak into a stunning landscape. You can feel the crisp air and the direct sun heat beating down on Afghanistan and from the air the geography looks amazing.

CoD: Black Ops also had a helicopter mission giving the player complete control. Having played both of them for this retrospective I actually have to give it to Medal of Honor. The Black Ops helicopter run while fun at the start devolves into a comical amount of destruction. Medal of Honor’s Apache run is fast and fluid, striking at a few targets then moving on. They know they are outnumbered so they move quickly and strike hard, which is what an on-rails shooting segment should be.

As the Apaches finish up their mission and cross back over a ridge they notice just too late that there is an anti-aircraft gun aiming at them. As they brace for impact a shot rings out across the valley hitting the anti-aircraft gunner in the head and disabling the system.

The Apaches say thanks to whoever it was as we switch back to the Delta boys of Dusty and Deuce, sniper rifle smoking from their shot. I really like these level transitions, they give this sense of a fighting force who each have unique skills and being able to click together on the battlefield. Nearly every mission until the end includes these transitions and they really add something to the narrative.

Back to Dusty and Deuce who are slowly and methodically taking out mortar encampments and foxholes. It’s alright, but there is not really any skill to it, no holding of the breath and only slight wind movement to factor in.

The mission does heighten up though when nearby claymores go off, indicating to Dusty and Deuce that enemies are closing in around them. Switching to your sub-machine gun, Dusty tells you to strike when the time is right. You choose when you starting firing, letting enemies get closer for easier shots or far away for better cover.

Dusty realises the forces are going in a different direction so Deuce pulls out the sniper again and sees Mother, Voodoo, Preacher, and Rabbit also being overrun by Taliban fighters. Deuce begins to pick off enemies and this time the sniping is relatively fun. It’s moving targets, covering our allies, it feels urgent and conveys it well.

Another excellent transition into the next mission, where we travel across the canyon into the shoes of Rabbit as the rest of the team make their controlled retreat.

As there are only four member of the team, the squad has to “pepper-pot”; lay down suppressive fire and wait until their teammate is in a position to take over, then turn around and sprint down the mountain until they can take over again. It’s a great sequence, all player driven, either the enemy overwhelms you or the NPCs say you’re ready to move and I would be happy seeing it replicated in other games.

The team continue to retreat down the hill, while helicopters and bombing runs try to keep the Taliban at bay. Yet the Taliban have brought RPGs with them, so repeat runs are called off, leaving Neptune at their mercy.

Voodoo dislocates his shoulder in a fall so he and Rabbit swaps weapons, Rabbit taking the M60 machine gun. The new gun changes the rules of engagement; with the previous rifle it was tight shot placement, but the M60 allows for more liberal covering, similar to the Rangers a few missions ago.

A Chinook lands to collect the team before they are overrun. While Mother and Rabbit make their way onto the helicopter, it is struck by RPG fire and takes off early leaving Voodoo and Preacher behind.

It’s a great scene, all done in-engine, watching the two small dots of Voodoo and Preacher retreating while seeing the never-ending stream of Taliban fighters following after them, Mother shouting at the pilot to turn around.

Mother and Rabbit are ordered back to base by the General but the two disregard and reinsert at the top of the mountain side, playing the same cutscene from the opening.

The screen flashes up “Day 2”, a little reminder that the team has been on-the-go for over 24 hours at this point. It harkens back to the numbered days in CoD campaigns, but if the timestamps at the beginning of levels had also included the day, it might have worked. The fact it only says “Day 2” now, two levels before the end, it feels like an afterthought, needing to place it somewhere in the story but not actually placing it with purpose.

Back to the gameplay, the helicopter starts taking fire and Mother and Rabbit have to jump out while the Chinook goes down. Jumping from the helicopter takes its toll on Rabbit though. He coughs up some blood as he stumbles into cover with only his knife and pistol as his weapons, his night-vision goggles damaged and displaying static every few seconds.

The stumble of Rabbit, which I thought to be part of the cutscene is actually the movement speed of the level, changing how players react. It’s novel and interesting playing a wounded solider having to continue into a firefight.

Atmosphere in this level is top-notch. The howling wind, the dark rock formations, the stuck-solid snow and ice on the ground with limited weapons and poor visibility, the game does a tremendous job of making the player feel totally isolated and alone. CoD at the time had never really done a mission like this; being hunted yet sticking to slow movement and silence, so props to MoH for giving us a unique level.

Rabbit starts to make his way towards the summit, knifing people here, silently shooting others there. He soon regroups with Mother and the two sneak by squads of fighters. They eventually get spotted and Rabbit has to resort to taking enemy weapons to keep himself stocked on ammo. Again, something new, having depleted ammo stocks and having to keep your eyes open for new weapons all while taking fire.

Rabbit accidentally sets off an IED, leading Mother to drag him away to cover while Rabbit gives covering fire. Obviously inspired by the chaotic ending of MW2’s “Loose Ends” mission, this one manages to keep pace with the more bombastic CoD. Small fires dot the landscape, seeing enemy silhouettes breaking through the smoke, only using the pistol, it’s all great stuff.

The two members of Neptune have to retreat, dropping their weapons and sprinting down a mountain path. They reach a dead-end, and decide to trade “broken bones for bullets”, jumping off the mountain in the hopes of escaping the Taliban. The two throw themselves into the air, tumbling down and sadly being quickly surrounded by Taliban fighters and taken away.

As the duo are led away the base can only watch on video link via a drone. We see one more call with the US-based General, who is mad that Neptune disobeyed orders despite the Colonel at the base trying to explain their actions.

The Colonel wants to send in the Rangers as back-up, but the General is adamant that no other forces head up there. The argument gets heated until a communications officer hangs up the video call with the General (claiming “network interference”), leaving the Colonel to order the Rangers up the mountain after Rabbit and Mother.

It’s all very Hollywood and I’m sure if anyone actually did this in real-life they would be court-martialled within a second, but as a way to get us into the mood of saving our boys, I’ll let it pass.

Back in the boots of Ranger Dante Adams for the final mission and our infiltration to the top of the mountain goes as well as our drop off into the wadi. The Chinook takes on fire, bullets shredding the inside of the aircraft and killing several team members.

The helicopter crashes and we are dragged to our feet by our Sergeant, telling us to man the door-mounted chaingun. It’s a short but fun segment blasting away the enemy forces, the gunfire actually felling trees due to the power and rate of bullets being fired.

We are soon told to move and continue the fight outside. It’s very reminiscent of the previous Ranger mission, of being hopelessly outmanned and hoping that tactics and weaponry can solve the imbalance.

One of the other soldiers asks about the SEALs and the Sergeant responds, “We need to unfuck this situation first.” The dialogue for the game hasn’t been terrible, nothing meme-worthy nor truly memorable, but this line is great; it’s believable and shows the differences between the calculated SEALs and the reactionary Rangers.

As we are escorted out the helicopter, the music begins a slow and mournful violin melody underscored by sad cellos and dark double bass’. The music is composed by Ramin Djawadi, composer for System Shock 2, Thief II, Gears of War 4 and 5, and most famously Game of Thrones, for which he won two Emmys.

Early Medal of Honor and Call of Duty games usually had great orchestral ensembles, military-style brass and drums with evocative strings and woodwind emulating the soundtrack to Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (the film that inspired the whole genre as Spielberg and his game company, Dreamworks Interactive, created Medal of Honor with Spielberg writing the storyline. Danger Close, the developer of MoH 2010, is a rebranded Dreamworks Interactive).

CoD’s soundtracks became very modern with heavy use of synths, drums, and in the case of World at War, anachronistic electric guitars and voice modulation.

It could have been easy for Medal of Honor to also take this approach but Djawadi goes mainly with the classic orchestral style instead. The score’s best moments are these sporadic yet beautiful violins solos like the one that accompanies us up the mountain. Another one plays during the previous Ranger mission before the Apaches come to the rescue.

It perfectly envisions the lone soldier; enduring battles and injuries, the rise and fall of combat, the thin air at the mountain top, and is a wonderful touch as the mission continues.

As the team make their way up the mountain they find a foxhole and split up. The radio man and another private head back to the helicopter for more reinforcements and the sergeant and Adams decide to head into the foxhole.

Despite this being the final level and having made my way through all sorts of different landscapes in the game, entering the foxhole actually made me anxious and I think its all down to playing as the Rangers.

When you play as a member of the SEALs you know they are the best of the best. They run towards danger and and experts at flushing out enemies and putting them down quickly.

Rangers, or at least general boots-on-the-ground soldiers, it’s always felt more like a general securing-the-area/mass invasion force, using sheer numbers rather than skill to overwhelm the opposition. An example would be the mission “Charlie Don’t Surf” from CoD4. The US force is not the highly trained SAS, but it doesn’t matter because they use their hundreds of members to pacify their objectives.

So back to Medal of Honor, clearing these foxholes should be a job for the SEALs. Actually, we have cleared cave systems with them in an earlier mission. But since all we have at the present moment are the Rangers, they ready themselves to go in and clear it out.

The sergeant, Patterson (a nod to the playable character in the original Medal of Honor) is constantly telling Adams to keep up, repeating commands about shot placement and movement. It made me think that the Rangers know they are out of their depth and so fall back on their basic training to get through.

And Dante Adams, our player character, is only a Private rank. He’s probably had a few missions, but this could literally be his second time in combat. He could be an eighteen-year-old kid from Kansas who joined up to “put a boot in Bin Laden” and here he is going into a possible death trap.

It was a great and emotive feeling and I wish the game had done more of it. Have some down time in the base, meet your comrades, read a letter from home, something else to make these characters come alive.

Back to the actual gameplay, Patterson and Adams clear out the cave and find an exit on the other side where they meet Voodoo and Preacher also following the trail of Mother and Rabbit. Again, it’s a great scene with nice details being the different language used, (Patterson calls out “friendlies” and Voodoo calls out “blue” to indicate not to shoot).

The four make a impromptu team to head towards Mother and Rabbit and it’s a highlight of the game. It’s a multi-pathed trek up the mountain top, the sun glistening off the snow, Voodoo becomes interim team leader, he and Preacher calling out targets for Patterson and Adams.

A minute ago we were relying on Patterson to get us through tough times (the cave system), now he can rely on Voodoo and Preacher to protect him. Another nice bit of character is Voodoo calling them “sergeant” and “specialist”. It would have been easy to use their names or even slightly insulting languages like the other Rangers did; “ladies”, “losers”, “you two”. Instead, he falls back to the rank and role, a mark of respect despite he and Preacher obviously being the leaders of the operation.

The team finishes the campaign by finding Mother and Rabbit in another cave system with the final cutscene playing from Rabbit’s first-person perspective.

The team carries Rabbit back down the mountain to the downed helicopter that the Rangers arrived in. The Rangers mill about; they know they are out of their depth and the SEALs will say nothing, so they stand around remarking on Rabbit’s condition (“this carbon is really tough” says Pvt. Hernandez). Even Dante Adams leans in to say, “Hang in there, we got you.”

The SEALs try and stabilise Rabbit with Voodoo displaying uncharacteristic softness and tender care, repeatedly telling Rabbit he’s “gonna be okay”. It’s a great scene to show Voodoo’s range. Most of the campaign he’s very into killing people (sometimes brutally with his tomahawk) so it’s refreshing to see the manly SEALs displaying some emotional vulnerability.

Despite calling for a quick extraction the air force doesn’t have any transport standing by for the team, having to wait for birds to come from further away. Both Mother and Voodoo voice their issues explaining that Rabbit is going to die if he doesn’t get care soon as Rabbit slips in and out of consciousness.

As the birds finally fly overhead, Rabbit’s vision blurs and we transition to the inside of the helicopter. The radio call says “eight heroes aboard”, but there are only three SEALs sat at the back of the helicopter. Their brother-in-arms lies at their feet.

They watch on as fast jets bomb the mountain hideout to kingdom come, before Preacher reaches down and fishes out Rabbit’s lucky charm (obviously a rabbit’s foot, but the first time we ever see it), before agreeing with Mother that “this isn’t how it ends.”

And then the game ends.

Well, not immediately. There is a six paragraph endnote thanking servicemen and women of past and present for defending freedom and highlighting the secretive and violent work of the Special Forces. It then cuts to a short teaser for the next game (an out-of-context scene two guys sitting at a cafe and nothing else) and then credits roll.

The first time I played Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare I distinctly remember getting weirded out by its depiction of war and how cool it thought it all was. Was it disrespectful in reflecting very real and recent events or was it just cold?

With age I see it is the latter and the graphics, sound, and content give it high-quality verisimilitude, confidently depicting the war some had experienced or at least seen nightly on the news screens. It highlighted the intensity yet never stepped into overblown outlandishness.

Medal of Honor carries that torch. It’s what suckered me into giving it a go. I was never an online gamer, so a single-player story was all I had to look forward to. That initial elevator pitch of real-life stories in Afghanistan, of authenticity, it sold the concept to me. Fifteen years on, it’ll still be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of the game.

MoH follows CoD4’s blueprints throughout the game; its heroes are soft-spoken and rarely depicted as frat-bro stereotypes. Tasking players as part of the team, sometimes point-man, sometimes support. Giving players overpowered weapons to destroy their enemies, but then making them fearful of ambushes and having to crawl around the opposition.

MoH is calmer than Call of Duty: Black Ops or Battlefield: Bad Company 2, its direct competitors at the time. But I think that calmness, a lot of players felt it was lacking exciting gameplay. CoD4 spawned an entire genre that in turn cannibalised it. So when Medal of Honor appeared three years after the hype train it felt like the most generic of all FPSes from the seventh generation.

And to be honest when I first started replaying, that was my thought. There was a moment where I asked myself “was this worth it?” Would going through this game give me anything new that I hadn’t seen before? And luckily that’s when the Rangers came in. It’s a shame that the best missions are towards the end because any player who is not 100% wanting to see the credits will probably give up before then.

Beyond 2010, Medal of Honor only released two games in the following ten years. 2012 saw the release of a direct sequel, Medal of Honor: Warfighter, a name that has been memed to hell and back and a game that really doesn’t have much going for it.

Players take control of Preacher (the only member of Neptune without any characterisation in 2010) and weaves a tale of both the personal struggles of married life with a convoluted “follow-the-trail” storyline.

It looks stunning with photorealistic models (apart from Preacher’s daughter, who has a weird haze around her face) and features locations such as a flooded city in the Philippines, abandoned Winter Olympics arenas in Sarajevo, and the bustling streets of Pakistan, all powered by Frostbite 2.0.

But the story…I will give it props that actual active Navy SEALs were brought it to lend it authenticity (for which they were later disciplined for revealing classified information), but it’s a non-linear mess with the most tenuous of links between locations and missions.

The second game, Medal of Honor: Above and Beyond, was released in 2020 for VR devices by Respawn Entertainment, being a major seller according to Steam and one of the most expensive VR productions according to Oculus, but mixed critical reception.

Danger Close were the developers of Medal of Honor and its sequel Warfighter. Previously named Dreamworks Interactive and EA Los Angeles, Medal of Honor was only their second game as the new outfit.

Then three months after the release of Warfighter, EA pulled Medal of Honor “out of rotation” and closed Danger Close, a sad end to a genre-defining studio. Once a market and creative leader, Medal of Honor had fallen and didn’t make its way back into the mainstream.

One wonders if it will ever come back. CoD has kept reinventing itself with titles that could be described as high-budget sci-fi epics, avant-garde Cold War thrillers, and buddy-cop-feminist-alt-history gems.

Battlefield has run the gamut from beloved to boycotted within one sequel (Battlefield 1 to Battlefield V).

Medal of Honor released at the wrong time. A few years earlier, it might have caught the wave. A few years later it could have taken both CoD and Battlefield as they were languishing in creative mires. But in 2010, CoD was king and MoH couldn’t stand toe-to-toe.

It’s sad to not see Medal of Honor around. Modern Warfare CoD has been mocked for its stories, all four-dimensional chess battles between Captain Price and Makarov. Battlefield’s single player is always too short and sometimes neglected all together in service to the multiplayer.

There is space there for a strong narrative-driven shooter, and Medal of Honor with its focus on true stories and real-life events could corner a section of the market that looks for something a little deeper in a shooter.

I respect Medal of Honor 2010. It did something new and creative in one of the most saturated genres at the time and that second half has some of the best levels I’ve played in a military FPS.

If you decide to pick it up, give it a chance, and it might surprise you into enjoyment too.

Banner Photo Source: YouTube, “The Virtual Commute”